Becoming a trans activist

Please note that the topic of this podcast might be triggering for some listeners. Feel free to skip this episode if this is difficult for you.

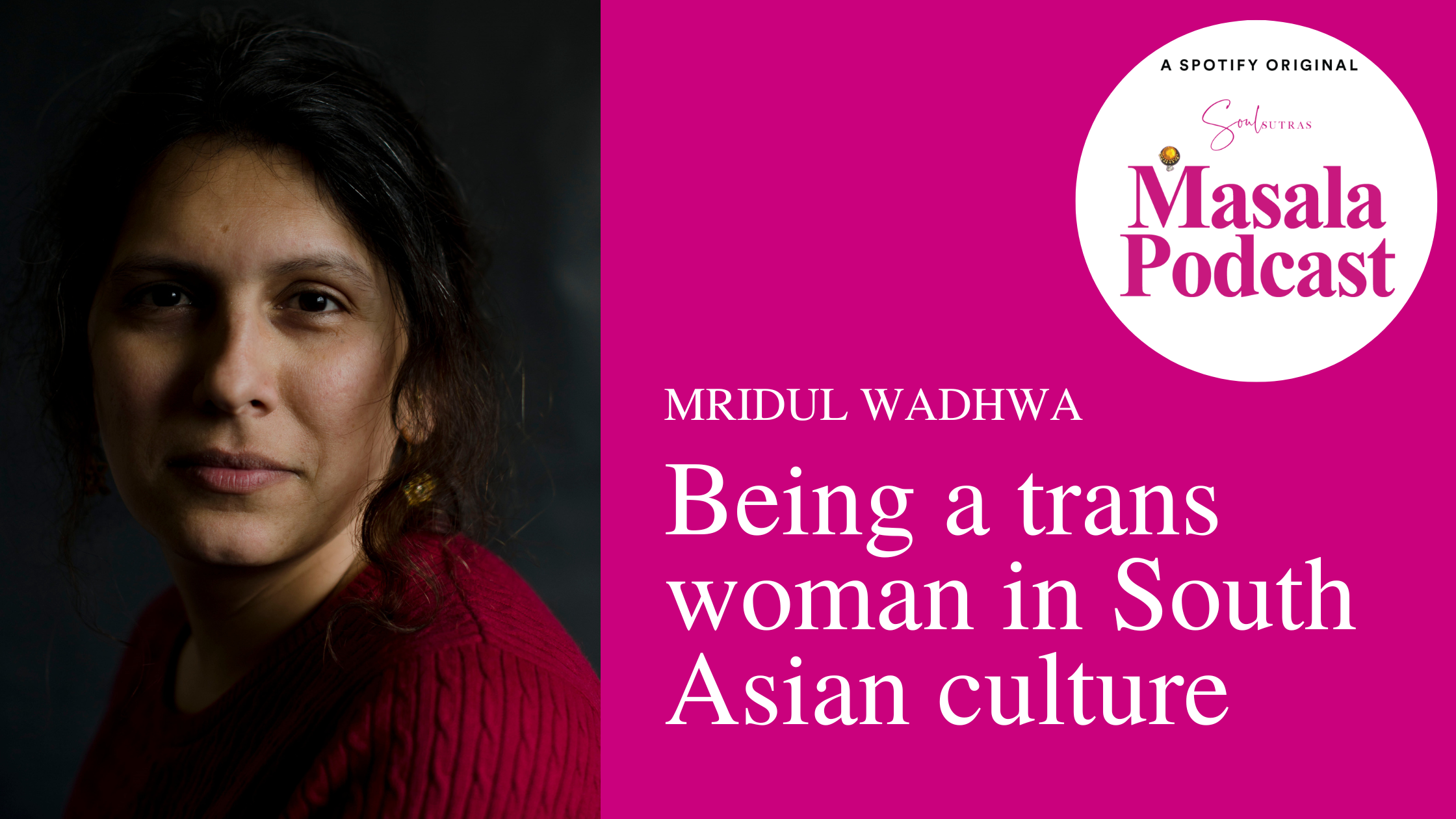

What does transgender activism look like? Meet my guest on Masala Podcast, the incredible Mridul Wadhwa (pronouns she/her). Mridul is a transgender woman who grew up in India and now she uses her voice in the Violence Against Women sector and is an inspiring activist.

In this episode of Masala Podcast, Mridul shares what it was like growing up in India as a trans woman until she was 27. And discovering the meaning of being a transgender woman in traditional Indian society.

Mridul talks so openly about her life in India and her difficult childhood. She speaks so eloquently about the violence she experienced in her life, her transition journey and all the difficult paths she had to navigate along the way.

As a survivor of violence & as someone who has navigated some very rough roads, I am blown away by how much Mridhul had to overcome and how she’s dedicated her life to helping others who have experienced physical, mental and sexual abuse.

Today, Mridul Wadhwa is the Chief Executive Officer at the Edinburgh Rape Crisis Centre, which offers support to women, the trans community, non-binary people & young people 12-18 who’ve experienced sexual violence at any time in their lives.

Mridul Wadhwa who calls herself a trans migrant woman from India has worked in the gender based violence sector in Scotland since 2004. I hope you enjoy this episode as much as I loved talking to Mridul.

RESOURCES FOR TRANS & NON-BINARY FOLKS

Here is a small list of resources. If you have any others that you think would be useful, please share via email and I’ll add here.

Mridul Wadhwa on Masala Podcast: Transcript

Sangeeta Pillai 0:00

This episode contains discussions that might be triggering for some listeners. So please feel free to skip anything that you may find disturbing. And also, do check the show notes for support. I’ve listed some organizations and resources that you might find useful.

Mridul Wadhwa 0:19

I was this very effeminate, young child who, you know, like the world tried to see me as a boy or kept telling me that I was fun, but I did not see myself as one and also, I believe that they didn’t see me as one either. It was just that is what was expected because of what lay between my legs really,

Sangeeta Pillai 0:57

I’m Sangeeta Pillai and this is the Masala podcast, the Spotify original. This award-winning feminist podcast for and by South Asian women is all about cultural taboos, sex, sexuality, periods, mental health, menopause, nipple, hair, shame, and many more taboos. Join me around my virtual kitchen table as I talk with some inspiring women from around the world, exploring what it means to be a South Asian feminist today. On this episode, I talk with Myrtle Vaudois, Chief Executive Officer at the Edinburgh rape crisis center. Riddle calls herself a trans migrant woman from India, who has worked in the gender-based violence sector in Scotland since 2004. I loved chatting with brutal she talks so openly about her life in India and her difficult childhood. She also speaks so eloquently about her transition journey, and all the difficult parts she had to navigate along the way. I hope you enjoy this episode.

Mridul Wadhwa 2:16

So, I grew up in India, in a city called Pune and I lived in Pune till I was about 27 years old. And I grew up in this home, which was on the most wonderful street that you can find in our city, it was called synagogue Street. And one end of our street was a synagogue, and the other end was a Zoroastrian Fire Temple. And in between all of that, there was an imam Baraka, a mosque, a small temple, or Sufi Durga, a Catholic shrine. So, I grew up in this very sort of interfaith neighborhood, but also in an interfaith home.

My mother’s is a Russian, Iranian, and my dad is a Sindhi, so I have a sort of history of refugee that like, my grandparents, and great grandparents were refugees to India, from what is now Pakistan and Iran, you know, as a trans child, and as a trans woman, it was not a pleasant life, I have to say. There was a lot of violence and harassment, but I still have very positive memories of my home, the home, it doesn’t exist anymore, but the home that I grew up in, and recently I was thinking about that home, and because it’s almost sort of mango season, we have this big mango tree that shaded our home, and I have many memories of sitting under that mango tree, claiming it eating the mangoes from that tree, you know, right in the heart of, of urban Pune, there are good memories. And what I would say was quite a violent childhood.

Sangeeta Pillai 4:03

Of course, and I completely get it. Some of my memories of growing up in India. Some of them are quite idyllic, but a lot of them are difficult, but I don’t think one cancels or the other. So, I completely get what you mean. When you talk about the mango trees or the temple, and the mosque and everything together. Would you talk to me a little bit about the violence in the home that you mentioned?

Mridul Wadhwa 4:27

Yeah. So, my parents have what we would call an India love marriage. And I think particularly in South Asian communities, people just still talk about it in those terms. I think it was quite unusual in the mid-70s to have an interfaith marriage. There was still quite a significant taboo attached to the Russian women living in India marrying outside their faith. So, my mom was the second in her family to have married outside the faith, but the consequences for her were less dire than they were for her and who had eloped and married and answer Russian men. So, my dad was welcomed into the family.

But in some ways, I think that was a trap for my mother, because I feel although they’re still married, they still live together. And I think, you know, just from reflecting on some of her, what she’s told me, not in great detail, but alluded to about her early life, I think that maybe at some point, after she got into a relationship with my father, she may have wanted to end it, but couldn’t because this reputation had been attached to her that she was in a relationship with a nonzero Russian man, to somebody outside her faith, who her family had actually welcomed into their, their family. So, it was almost an entrapment, I would say, like her autonomy and her decision to leave or and that relationship really was no longer hers, because of this reputation that she had acquired.

So, I would say that my parents’ marriage was quite abusive, I don’t remember too many incidents of physical violence. But it was a course of controlling relationship, the level of control that my father and also his wider family have had on my mother’s life. And subsequently, her children that is ours has reduced with time and age, as I said, they still live together, and mostly have happy days. But there is a toll that it has taken on my mom’s confidence and her ability and my mother, quite a rarity for her community. And also, her time, she’s in her early 70s.

Now that she was a trained Kathak dancer, and there’s something wasn’t anybody in her family, or even her faith community at the time who, someone who had trained in Indian classical dance, and she was really, really good. And she is really good, she still dances. And I think one of the biggest sacrifices that she had to make after marriage was that she had to give up her, her dance, something that she could have had a professional career in. And slowly, I could see, you know, even as a child, how my mom’s life became smaller and smaller, and that she was no longer able to go out to work after she had my younger sister, there were three of us, even though if there were financial challenges in our home.

So, she found other ways to be financially independent. And, and I suppose within that environment, being a trans child being a child of an interfaith marriage, who I would say, like, there was an exclusion that we experienced, my siblings and I, and I, for me, it was double, because I was this very effeminate, young child who, you know, like the world, tried to see me as a boy or kept telling me that I was fun, but I did not see myself as one. And also, I believe that they didn’t see me as one either. It was just, that is what was expected, because of my, you know, what lay between my legs really. And so, in that experience of violence, or domestic abuse, actually, and I’ve said this before, in some ways, my chance SNESs was hidden, because we were all just mostly coping with the good days and the bad days of the violence. And, and because outside was also so dangerous for me, because I get to like, I was not a trans woman who could or trans child who could mask her gender identity, like I really worried and express myself as I was, but I went to an all-boys Catholic school. And so, there was violence everywhere, from name calling to physical abuse, and in slightly older life, sexual violence, sexual abuse, as well. So, despite the violence in my home, it was much safer than outside.

Sangeeta Pillai 9:11

So even if there was violence in the home, that was safer than what lay outside?

Mridul Wadhwa 9:16

Absolutely. Because outside it was hard to predict who was going to be violent. Whereas at home, it was much more predictable. And also like, my father wasn’t always at home. He worked away most days of the week in a different city. So, you know, we had periods of calm and peace when it was just my mom and the three of us.

Sangeeta Pillai 9:38

I mean, I’ve grown up in India, I’ve spent most of my life in India, and I know how difficult it can be when you don’t conform. And I should imagine that was really hard actually, being in a body that felt like it wasn’t if you came across as a feminist you know, there’s a lot of really high harsh, negative comments and what you mentioned, physical abuse. That’s horrific. And sadly, that’s part of our culture, I think.

Mridul Wadhwa 10:09

I think it’s part of most cultures particularly and how trans people are treated, and especially trans children who, as I said, who are out or who are, you know, even if they haven’t said the words or know the words to describe themselves as trans or as, as girls or boys, or as trans boys or trans girls or non-binary identities. As soon as you are clocked as one, whether it is true or not. And whether you are trans or not, the violence comes with it. In some ways, I suppose growing up in a family that had already sort of broken the norms, it trained you to learn to live on the outside, on the periphery, to be excluded. But there was a benefit, I would say in that, I think my whiteness, like I was a very attractive child as well, a cute one.

So, in the younger years, let’s say in primary school, and so on, it was tolerated within, my immediate circle immediate family, there was this expectation that we would grow out of it. And I would hear stories about other adults in my life, who used to play with dolls and dressed up as a girl or whatever, in their early days, and then they grew out of it. So that was definitely the expectation within my home. But obviously, that was not going to happen. As I grew older, went into adolescence and teenage hood, then obviously, it became more acute and the pressure to conform to masculinity was greater, but obviously, I simply didn’t know how to do that. I think one of the advantages of growing up in the two faiths that I did was that a sense of shame and guilt was not passed on in the way that faith was practiced within our home. I don’t remember. I’m sure they did. But I don’t remember my parents actively and consistently telling me to be someone who I wasn’t. Occasionally, yes, but it was not a consistent message. I didn’t feel like I was excluded from whatever love that they had to give me in whatever way that they gave me. Despite the domestic abuse, like domestic abuse is so complex, it’s always sort of mixed up with love and affection and so on. I don’t remember them telling me not to be who I was consistently, occasionally. Yes. But yeah, I was denied opportunities, I was denied the experiences that I wanted to have for myself as a young person because they were not deemed masculine.

Sangeeta Pillai 12:59

Growing up in South Asian culture, meant an explosion of colors, and sounds, and food and festivals. But for me, it also meant being told that I could only occupy a very small space because of the sex I was born into. I was a girl. So anytime I strained outside of that narrow space, I was told off. Don’t talk too loudly, they said. Don’t draw attention to yourself, they said. There were so many rules, and so many boxes. All of them small. All of them suffocating. One fine day, I decided to break out of that box. I was done with being told how loudly I could talk. How boldly I could laugh. I decided that my spirit was much too big to be contained in that little box. Do you remember the first time you thought about transitioning?

Mridul Wadhwa 14:28

Yes. I don’t know if you remember Sangeeta but there was this program that used to come on a Friday with Prannoy Roy?

Sangeeta Pillai 14:36

Yes. I used to be glued to it. I used to feel really intellectual watching it.

Mridul Wadhwa 14:42

Yeah, so it was a very popular program, I suppose in quite a few English-speaking households at that time. There was a story of I think the woman who acted, maybe she died recently, who acted in the James Bond movie, a trans woman and that was my first sort of real visual of somebody who had transitioned in the way that I would have liked to transition. And I can’t remember how old I was, I must have been around, definitely under 10, or close to 10 years old. It was at that time there was this idea that oh, this is possible.

There was another woman who was from the Parsi woman, she had transitioned in Bombay. She was a Zoroastrian woman, and my mom had told me about her, not me specifically, I heard her talking to one of my aunts about her, like she had seen her in the toilet at the Taj Hotel in Mumbai. And she was talking about her, and it was like, oh, this is actually possible. But most seriously, where I actually took steps to do something about it is when I became really actively suicidal when I finished the 10 standard, or when I finished school, I was 16 years old, I had become actively suicidal, because I really could no longer cope with this. Because my 20-minute neighborhood was no longer my 20-minute neighborhood, like I started going to college, which I purposely chose, like really far away from home to experience some level of anonymity where people didn’t know me, I mean, I was quite naive because the hate travels with me.

So, when I went there, there was, again, bigotry and hatred and sexual harassment, and which, of course, no one would believe that I could be sexually harassed, but I was at the time, and it just got a bit too much. So, I remember writing a letter to my mother explaining who I was, and what I wanted to happen. And to her credit, although my mom didn’t really acknowledge the letter directly in words, or anything like that. But she spoke to my grandmother and my grandmother’s sister. So that’s her mom and her mom’s sister. And they took me to see doctors, okay, like a pediatrician, who then got me to see an endocrinologist and a psychiatrist. And it was very clear to me that while my family were concerned about my health and safety, they were all looking for an answer, which seemed to suggest that I would grow out of it, that it would pass.

And also, like, the doctors also didn’t believe me, because what they looked at, when they looked at me was to see if I was intersex, which was very much the sort of prominent understanding of the Hijra community is the Hijra community being intersex community, which isn’t entirely true. But that’s what they wanted to know, if maybe I was intersex, and therefore, saw myself as a woman. So, there wasn’t anything educated from my perspective around what it means to be trans. And I felt quite powerless in that experience because I didn’t have the resources. But also, I felt acknowledged at the same time.

But when they got the answer that there wasn’t anything wrong with me. And the doctors said that I would grow out of it, then there was this whole silence again. But I realized soon after that, this was not the life I wanted to live not at the mercy of, of my family, or of my elders, or our people who were meant to be protective factors. So, I think I embraced my adulthood, and just decided that the only way I could live life on my terms is if I, if I was honest about who I was.

So, after that experience, and a year later, I would say I, when I finished college and went to a study at university, I did a diploma in hotel management, I decided that I would tell people who I was exactly that I was a woman was a trans woman. And as soon as I had the resources, I was going to transition. And that’s how I decided that I would speak about myself to the world, because they were making many assumptions about who I was and what my identity was based on how I presented. So, I decided that I would take control of my narrative. And life changed quite dramatically after that, I have to say.

Sangeeta Pillai 19:33

When you finally transitioned, what was your family’s reaction?

Mridul Wadhwa 19:40

So, over the years, I definitely changed the balance of my relationship with them, because I had become financially independent and they knew that I live life on my terms, even though I lived in their home. It’s all very respectful and loving, but there was a real mental block for them around this transition. And, and they had, in fact, the psychiatrists who did the psychiatric evaluation, which was needed to be able to have the surgery, had asked to speak to my parents, and they were very clear to me that it wasn’t because they needed to double check or, or verify my story as it happened in a previous experience with a psychiatrist. And they, they said that they, they thought, given the Indian context and the South Asian contexts and the family dynamics, it would be safer and better if they explained us, as this team of psychiatrists to my parents and my grandmother of what was going to happen. So, they did.

And then after that my parents had called his family meeting, which I was subjected to like an intervention with some of my other relatives, you know, I woke up in one afternoon after doing a night shift, and they’ve all these relatives were there, they were all there to talk me out of transitioning, trying to suggest to be hard visible my life would be, and then I had to tell them some really difficult truths. So, you know, for a long time I had hidden from them, or never really spoken to them about the violence that had experienced, particularly the sexual violence and physical violence, because they were trying to explain to me that there would be so much violence that would come with transitioning, and I was like, well, I was already living it.

So, I don’t know what they were trying to protect me from. And I think the forests with which I was able to retort back and be absolutely clear to them that they were not going to change my mind. And it was their choice, whether they wish to see my life or not. That’s how I won my family over. It wasn’t I still didn’t know till the day before my site, or two days before my surgery, where my parents actually stood, whether they were going to be with me, I knew that they loved me. And I knew that they worried about me, but you know, at some point, actions matter more than your words and your feelings. At that time, I was living with my grandmother, who was extremely supportive.

It was really interesting to see my grandmother and her siblings like she at the time, she had six of her sisters were alive. And five of them were extremely supportive off me, including all the other sort of the Russian women and my grandmother’s spicy colony in Puna. And so, I knew that I had her. But my father showed up at my grandma’s house. And he said that he had informed his family that this was happening. And he just wanted to know what he needed to do. And that was it. We didn’t look back after that.

But I have to say that, while it seems, and it has, it feels on most days of the year, that my parent’s love and acceptance of me is unconditional, it really isn’t because it is so rooted in stereotypes of womanhood, because, you know, as, as my body transformed with transition, as I went from cute boy to hot chick and how the world perceive me, my whiteness, the attractiveness, or the perceived attractiveness of my, of my being, you know, in a sort of heteronormative attractiveness, that made my transition more acceptable. But if I had not been able to leave the masculinity of my body behind, because it’s really quite hard to explain transitioning.

But one way of explaining it is like your soul, your inner being, your view of the world, my view was very woman. And it was my womanhood. Obviously, it’s not the same woman it is as yours or someone else’s. But it was my womanhood. And there are many things in common that we share in our womanhood, but it was my unique womanhood, because I didn’t grow up as other women. But I saw the world as a girl and a woman. So was my girlhood, my womanhood. But if I hadn’t been able to leave, you know, the, the impact of having a male body behind in the way that I have, in the most part, as I transitioned, I don’t believe that my the acceptance would have been the way it is now, because it’s still rooted in the superficiality of the body rich, rich, I think a lot of South Asian women will recognize like if I was a brown, dark skinned trans person, if I was not an English speaking trans woman, if I wasn’t from a faith community that is seen as westernized like particularly as a Russian, so and it was I would say this in the signs of my family. I don’t think I would have had that kind of acceptance, even from my family.

Sangeeta Pillai 24:56

Absolutely. And I know having spoken to other people that I’d say if you’re a dark-skinned person, say your family’s poor, say they don’t have access to, I don’t know, internet, textbooks to things like that. It’s a much harder journey, I think. So, I absolutely hear what you’re saying.

Mridul Wadhwa 25:17

I think class speeds such a significant role. So, while I didn’t grow up in money or with money, but we did have access to decent education, there was a history of wealth in my family, it’s just that my immediate family didn’t have it. So, we had those kinds of social connections that come with being from the faith community that I was, the Zoroastrian faith community, there were social capital from being part of a family that has a history of wealth, of living, in a in a big home, like I lived in a really big house for low rent, but there were these perceptions that gave you social capital. And if I didn’t have any of those things, I wouldn’t be sitting here speaking to you the way that I am. It’s really clear to me.

Sangeeta Pillai 26:08

The family you are born into, the home you are born into. These things are not in our control. And yet, these things have such an impact on the life we end up living. I was born into a poor family, a family that lived in a slum in suburban Mumbai. If you were to imagine how tiny our home was, just walk two steps around you. Two to the front, two to the sides, and two to the back. That was our home.

It was just one little room with enough space for a single mattress. We all slept in that room. All five of us. A miniscule bathing space, stood on the other end of the mattress. It was literally a hole in the floor for the water to go through. And that was my home for many, many years. I wonder if we could speak about violence, because it feels like just hearing your story and reading about you that the violence that you experienced when you were in a body that didn’t feel like yours, you know, being born male and feeling female. And then the violence that you experienced at home, within your parents, I’m sure has informed the work that you do today. But I wonder if, I think it’s important for people to hear what that lived experience feels like?

Mridul Wadhwa 28:10

I have to be honest, I’m not sure if I fully addressed the impact of the violence that I’ve grown up on in my life. I feel that maybe some of that is yet to come, addressing how it has impacted me, but you know, there is more and more clarity on who you have become because you have experienced violence. So, there are some positives, obviously compassion, and understanding a recognition of the journey out of violence or also the recognition that some people cannot leave those violent situations and that there is a sometimes a power in staying by choice or compassion, but also acknowledging that you’re being violated.

So, recognizing the complexity of how different individuals of all genders react to how violence has impacted them. I think the uniqueness of being a trans person has experienced domestic abuse or sexual violence and sort of violence in the community where no one in your community is safe. Like you don’t know if they’re actually going to become violent or not. And this is like the common experience of womanhood because there’s so many women out there in our lives, particularly in South Asia or South Asian women, even here in the UK, who are led to believe that anybody outside any man outside the home is violent and you know, like if the if you look at our experiences of Stranger violence, it’s not unusual for us to risk assess it.

Every relationship to see, how do I know this man is not going to be violent to me? I think what was different for me is that I was also having to assess how do I know that this woman is not going to be violent to me because of being before transition, I have to say, of being on that periphery. And you know, feminism has come a long way since those days, but you know, like, not knowing who was safe. Yeah. But I suppose the what is different about being trans and, and this risk assessment that most or almost all women I know do in relationships, particularly with men, whether it is a relationship of buying from a store regularly, you know, is this man going to make a pass at me, because I’ve laughed with him at the corner store, the local Asian shop here was that, once they realize that you’re trans, they reveal themselves so easily, they play their cards really quickly.

Because there is still a social license, I would say, across all societies, to be harmful to trans people. So, in some ways, that that risk of violence was also a gift in that I saw through quicker, who was who was going to be by who was safe and who was unsafe. Whereas I think for others, it may take a little bit longer, because people you know, they don’t reveal their harmful selves immediately, it takes a while. So that’s some of the impact.

But then there’s also the impact of disassociation, of disconnecting. And, you know, I have to cope with that, which is like a trauma, the impact of trauma, like I find myself often disassociating in situations, as soon as they become slightly stressful, so I have to really work hard to stay grounded to stay connected in the present, because the only way to cope with on street violence, when you’re experiencing violence every day abuse every day, whether it’s in the classroom, at school, from your peers, or walking down the street in your you know, like the disadvantage of living in a, in a small neighborhood, in a small world where the geography of your, of your childhood is so limited and small is that everybody knows you.

So, you know who is going to harm you as you walk down the street. And the only way to cope with that is to disconnect, take yourself away. And I suppose like, those are the things that have irreparably changed, and there are more negatives of that than positive. So that’s what I would say is the impact. And I suppose the work that I do, like I stumbled into it, I definitely did not come into working in the Violence Against Women sector, having done a lot of reflection and being very self-aware of, of how violence had impacted me, it was just like how I transitioned a series of incidents and opportunities presenting themselves and that’s how I started working in the Violence Against Women sector. And I’ve been working in it since 2004.

And it’s really, mostly most of my career was spent has been working with black minority ethnic women specifically, and trying to break down barriers, systemic or even individual barriers that professionals present in how minority ethnic women can access services, domestic abuse or sexual violence services. And now I work in a more mainstream service in a leadership role. It’s been transformational, like I don’t know if I can do any other work in any other sector. The further you are from the sort of sis heteronormative whiteness in the context of Scotland and the UK, the harder it is to access services.

Sangeeta Pillai 33:48

Thinking about it from a South Asian, female, and undefined point of view, it’s almost like a double-edged sword where if you don’t see yourself represented, it’s difficult to imagine that somebody might help you. And also, within the culture, it’s seen as harder, I think, from my experience anyway, to sort of accept that what is happening is abuse. Yeah, because that’s normalized to such a degree that, oh, you know, that’s just what happens in a marriage. That’s what just happens in a household. Emotionally. We don’t even have words to recognize emotional abuse, you know, physical abuse, okay. You can see somebody’s face is bruised or whatever. But the degree of abuse that happens within culture, and it’s kind of cut sanctioned, I think.

Mridul Wadhwa 34:31

Yes, absolutely. I think there is a real, one of the difficulties we have is that because everyone is telling you that you should just put up with these relationships, whether it is because it’s rooted in respect or tradition, and these very filmy dialogues that many of us grew up with, and I’m hoping that Bollywood movies I’m not saying that as much anymore, but you know, like something that I did carry with me, you know, about marriage in particular. Bollywood line from the 70s and 80s?

Sangeeta Pillai 35:05

For those who don’t speak Hindi is like you arrive in the marital home in the, I don’t know what the English word is, and you leave in a coffin, you don’t leave.

Mridul Wadhwa 35:17

You just put up with it and that message is consistent. Yeah, it’s almost systemically ingrained and you’re, whether it is the not the faith as such, but those who control the faith or whether it is elders in your family, sometimes your peers, the movies, you watch, all of that makes it so much harder to name what you’re experiencing, as abusive. Because if almost everyone is telling you like, this is just how it’s supposed to be like this inequality that you experience as women is just how it’s supposed to be.

And if that’s the loudest voice, then the whisper of women like us, it takes a long time for it to become a really loud voice in someone’s head. Yeah. And so for so many women, it is very much about if you choose to leave, or sometimes you’re not even don’t even have a choice, you just have to leave given the circumstances in which you find yourself, you also then have to leave behind so much of your cultural identity, your traditions, your temple, your mosque, your word via your church, you can’t go to the faces.

And I think where that differs from whiteness, in the UK context is that even if you leave and go as a brown person or a black person into a new community, then the Brown community is asking you, who are you? Where are you from? What are you doing here? And the white community is also asking you the same question. Yes. So then how do you recover safely? How do you, you have to sacrifice so much more, because I think, you know, like, it’s true for so many like former survivors, irrespective of ethnicity that when you leave, you leave behind so much. But when you’re a brown person leaving and leaving behind, if that’s what you have to do, you’re losing something, sometimes permanently, especially if you find yourself in a reserved space that is not willing to, to acknowledge the existence of divorced women or women who leave a forced marriages or leave their parents behind because they were abusive, or violent, and, you know, or, or singleness, or lesbianism. And there are so many, I’m just thinking, I’m holding somebody in my head at the moment, a young woman who had to give up all of that, and she had to give up so much more.

Because her life was so much risk, that she couldn’t even in public say, what her favorite food was, because that would identify her ethnic and cultural background. Like that’s what we have to lose sometimes. And I don’t think that is acknowledged, you know, saying that hundreds and 1000s of women in this country do that every year, they walk out of an n these relationships and embrace themselves and center themselves and think of themselves as valuable as important. And when you do that, I think the world might begin to see you as valuable and important. Not always. But the hope of that is there.

Sangeeta Pillai 38:31

That’s really powerful, isn’t it? To think that that act of leaving which feels dangerous, which feels difficult, which feels all of these things.

Mridul Wadhwa 38:40

It is dangerous.

Sangeeta Pillai 38:42

It is, not just feels Yes. But when you do that, the power that comes with it, I think, is I don’t know if we acknowledge that enough.

Mridul Wadhwa 38:52

And the power isn’t always visible immediately.

Sangeeta Pillai 38:56

That’s what I mean, not like the obvious oh, here’s a powerful woman but the power inside, I think.

Mridul Wadhwa 39:01

It takes a while before you recognize it in yourself after leaving, because you know, we know that leaving an abusive situation is much more dangerous than staying the rest of your life, and the loss of not just emotions and safety networks and relationships, but also loss of for many women and children. It’s the loss of practical things like becoming homeless, losing your job, losing your career, losing your wealth, if you had any. All of that, so much of time is spent in the early months recovering from that. But you do need someone around you, and this is where women’s organizations are so vital to reassure you that that actually there is a power in that there is hope in this and that it is possible. It’s not guaranteed but it is possible to have a better life. When you walk away from abuse in whatever way you choose to walk away and in sometimes For some women, it might mean that I know that this is abusive, and violent. I know I can’t leave. And this is, you know, like, this is controversial. But now I am letting this happen to me. And there’s a power in that, too. I think like, I think we should acknowledge that. Because I grew up with a whole generation of women who, around me, not just in my family, but in my community or the, you know, in the small geographical world that I lived in, who were in awful situations. But they were powerful. Despite that, they knew they couldn’t leave for so many reasons, mostly because of gender inequality, and lack of education, lack of resources, and so on and so forth. Although they stayed, there was a power or there was something really powerful in how they, how they manage that violence in which they were living in, and how the rebels in whatever way that they could we hardly embrace their inner Kali, you the Goddess Kali.

Sangeeta Pillai 41:05

Yeah, absolutely. And I think that aspect of it, I don’t think is acknowledged enough. I don’t think the kind of more glamorous face of a survivor is the one who leaves and makes a new life. But sometimes I think the survivor is the one who stays as well. And I don’t think we think about that or talk about that enough.

Mridul Wadhwa 41:26

I think we acknowledge that in the women’s movement, I would say no, definitely and, but I think as a community, we need to talk about it more, and acknowledge it more. And I think that if we if we are able to speak about that with compassion, maybe those women will be able to find the strength to end those abusive situations or find a way of breaking the sort of breaking the generational trauma that comes with staying, you know, trying to find a different life for their children or, or others that they might have, you know, carrying responsibilities for. I think that happens as well. Even for women who stayed.

Sangeeta Pillai 42:09

On that really powerful note, thank you so much for being on Masala podcast. Thank you for being as open and generous and kind as you have been. I look forward to following your work more and more. And thank you.

Mridul Wadhwa 42:23

Thank you for having me.

Sangeeta Pillai 42:28

Thank you for listening to the Masala Podcast, a Spotify original. Masala Podcast is part of my platform, Soul Sutras. What’s that all about? Soul Sutras is a network for South Asian women. A safe space to tell our story, to hear inspiring South Asian women challenging patriarchy, a space to be exactly the people we want to be and still feel like we belong in our culture, and our community. And ultimately, a space where we feel less alone. I’d love to hear from you. So do get in touch via email at soulsutras.co.uk or go to my website, soulsutras.co.uk. I’m also on Twitter, and Instagram. Just look for Soul Sutras. Masala podcast was created and presented by me, Sangeeta Pillai produced, by Anushka Tate, opening music by Sonny Robertson.

MRIDUL WADHWA ON MASALA PODCAST